Between June and October, visitors to Hemkunt and the Valley of Flowers travel from the plains into the hills by bus, by car, by truck, by scooter, by bicycle, even by foot. For the final two days of the journey, some walk, some are carried, and some ride mules. A few visitors make the journey individually, and more come in small groups with friends and family. The majority of Sikh visitors, however, come as members of large groups known as jathas. They are comprised of related families, of club members, of people from the same neighbourhood or from the congregation of the same gurdwara.

Most visitors first access the Uttrakhand region from Hardwar, the 'gateway to God', or from neighbouring Rishikesh. Both towns are situated on the banks of the Ganges where the plains meet the foothills. The road toward Hemkunt winds northward through the valley in which the Ganges flows, passing the Panch Prayag, the five sacred confluences where major tributaries join the Ganges. When it passes the last of these, the road continues alongside the Alaknanda river, tracing the ancient paidal yatra (walking pilgrimage) route to Badrinath. Located near the river's source, Badrinath is the most important Hindu shrine in the Himalayas. Because of its proximity to the border with China, the Indian army has gradually extended the motorable road to this pilgrimage centre, easing pilgrims' journeys.

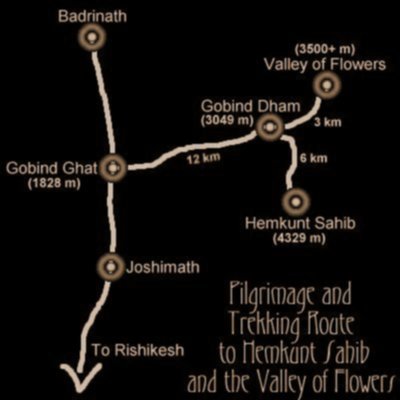

Thirty kilometres before Badrinath, and more than 250 kilometres beyond Rishikesh, the road passes the base of the footpath to Hemkunt and the Valley of Flowers. Vehicles can cover the distance in twelve hours. For those few pilgrims who walk from the plains, the journey to Hemkunt takes forty days. All need to stop for one or more nights along the road. Sikh gurdwaras, managed by the same trust that oversees the operation of the pilgrimage to Hemkunt Sahib, offer food and lodging in Hardwar, Rishikesh, Srinagar, and Joshimath.

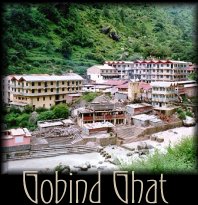

The path leading to both Hemkunt and the Valley of Flowers

begins from the village of Gobind Ghat (1,828 m), the

'riverbank of Gobind', built on the west bank of the Alaknanda.

Locally known as Simtway, it is not a permanent village.

Rather, it is a cluster of buildings housing hotels, tea shops, and

stalls which sell running shoes, plastic raincoats, walking

sticks, and souvenirs. They are open seasonally, when the

weather is warm and the path to Hemkunt is clear of snow.

The path leading to both Hemkunt and the Valley of Flowers

begins from the village of Gobind Ghat (1,828 m), the

'riverbank of Gobind', built on the west bank of the Alaknanda.

Locally known as Simtway, it is not a permanent village.

Rather, it is a cluster of buildings housing hotels, tea shops, and

stalls which sell running shoes, plastic raincoats, walking

sticks, and souvenirs. They are open seasonally, when the

weather is warm and the path to Hemkunt is clear of snow.

The narrow stretch of pavement leading to the main part of the village descends from a small upper bazaar along the main motor road to Badrinath. The buses stop here, letting off pilgrims, workers, and supplies amid several tea shops. All walk down toward the river. There, ghats (steps down to the water) have been built for those who wish to bathe in the sacred Alaknanda. Together with the name of the Guru in whose memory the pilgrims undertake the journey, these ghats are the village's namesake.

Near the suspension bridge that crosses the Alaknanda where

the footpath to Hemkunt begins, the gurdwara complex looms

large on both sides of the road. The buildings are white, and

their corrugated steel roofs, painted red and green, sport saffron

coloured flags which flutter atop storey after storey of

blue-shuttered rooms and halls. Pilgrims are accommodated

inside, along with other visitors who, regardless of their religion

or country of origin, sleep side by side with the Sikhs on the

stone floors. The gurdwara also offers simple meals and

luggage storage facilities to all travellers at no cost. Of those

who stay overnight at Gurdwara Gobind Ghat, or in nearby

hotels, many attend an evening Ardas (prayer service) in which

requests are made and thanks is given for successful journeys

Near the suspension bridge that crosses the Alaknanda where

the footpath to Hemkunt begins, the gurdwara complex looms

large on both sides of the road. The buildings are white, and

their corrugated steel roofs, painted red and green, sport saffron

coloured flags which flutter atop storey after storey of

blue-shuttered rooms and halls. Pilgrims are accommodated

inside, along with other visitors who, regardless of their religion

or country of origin, sleep side by side with the Sikhs on the

stone floors. The gurdwara also offers simple meals and

luggage storage facilities to all travellers at no cost. Of those

who stay overnight at Gurdwara Gobind Ghat, or in nearby

hotels, many attend an evening Ardas (prayer service) in which

requests are made and thanks is given for successful journeys

In Gobind Ghat, travellers can hire mules, porters, and sedan chairs. The porters come from Nepal each visitor season to work along pilgrimage routes in the Indian Himalayas. If there is insufficient work carrying loads, they are hired by local contractors to do other types labour: breaking rocks, building walls, and mending paths. Kandi wallahs are porters who carry baskets woven from bamboo and supported by straps across their foreheads and ropes over their shoulders. A kandi basket can be laden with backpacks, suitcases, bags, children, and aged or unwell visitors. For those visitors unable to sit on a mule or in a basket, dandi wallahs, in groups of four, bear them up the slope in wooden sedan chairs supported by poles.

Though they were traditionally herdsmen, all but a few the local hill people have given up this occupation in favour of opening businesses which service the pilgrimage and tourism industry. As a result, of the more than a thousand mules and horses that work the route to Hemkunt carrying people and supplies, most come from the plains. They are herded up the highway at the start of the visitor season, and back down again at its end. Of the men who own and care for these animals, most are also from the plains, and differ culturally and linguistically from the local hill people, the tourists, and the pilgrims.

Depending on the volume of visitor traffic on a given day (and on how much the visitors are willing to pay), the price of hiring a mule varies. The ghora wallahs, the men who walk with the mules, stand at the trail head with their animals, and call out "ghora, ghora, ghora" to everyone who passes. Mules can also be hired further along the path, at places where walkers may decide they are too weary to continue on foot. I heard one ghora wallah joke with a customer that she was hiring the services of a pahari Maruti. Pahari means 'of the mountains' and Maruti is a make of car. The man was, of course, referring to his mule, which to his mind was a "luxury ghora". He insisted that this justified the high price he was asking to hire it.

The mules add both colour and sound to the journey. They are decorated with red, yellow, and blue tassels. Bells around their necks jangle as they walk. And the men who urge them forward whistle, shout, and prod them with sticks, while at the same time yelling for those walking up ahead to move to the side of the path.

From Gobind Ghat, visitors cross the suspension bridge and begin their slow ascent. From there, the footpath can be seen as it zigzags up a steep hillside. After two kilometres the path levels out and begins to follow a stream which tumbles over boulders from its source in the Valley of Flowers and Hemkunt lake, on its way to meet the Alaknanda. At intervals all along the route are clusters of tea shops set up by local villagers and Nepalis. These shops are housed in temporary structures made of wooden boards and branches roofed with plastic sheets over bamboo poles. The proprietors provide long benches for travellers to rest on. In addition to tea, they sell hot snacks, coffee, and an assortment of cold drinks, biscuits, sweets, and chocolate bars. Visitors often express their surprise at how many packaged foods and drinks are available along the route. Some complain that the simplicity of the pilgrimage has been lost; that it is now possible to have your Coke even in the most remote region of the Himalayas.

The path, which is constructed from stones painstakingly set into the earth by hired labourers, is wide enough for two laden mules to pass each other. Finding footing on the stones is difficult for both mules and humans, but the stone surface is necessary to keep the path from degenerating to mud during the monsoon rains. Tacked to trees and tea shops along the route are signs with Sikh devotional messages printed on them in Punjabi and English. They also serve as advertisements for the businesses or organizations that put them up. At intervals, pilgrims are reminded by other signs, painted on rocks, to utter "Waheguru" (Wondrous God) and "Satnam" (The Name of God is Truth). Most graffiti, however, commemorates the visits of individuals and groups by displaying their names and the years of their visits, and sometimes Sikh symbols, in brightly coloured paint.

While I was doing my research, one jatha undertook the seva (voluntary service) of posting hundreds of stickers on tea shops, and even on the saddles of passing mules, reminding visitors that smoking is prohibited along the route (Sikhs, by commandment of their tenth Guru, abstain from smoking). Another group of pilgrims painted signs and posted bulletins asking people to keep the route to Hemkunt Sahib clean. Although it is a sacred place, the amount of garbage strewn alongside the path increases every year.

The sense of community among pilgrims is apparent everywhere along the route. When Sikhs pass each other they utter the affirmation "Waheguru ji ka Khalsa, Waheguru ji ki fatah" (The Khalsa is God's, Victory is God's). Many also encourage one another as they walk, saying that God will give them strength; they cannot feel weary because with every step they are getting nearer to the Guru's tap asthan (place of meditation). Pilgrims descending commonly distribute glucose powder, sweets, cardamom, sugar crystals, nuts, and dried fruit to those climbing upward. These are given to Sikhs and non-Sikhs alike, and to the porters and men who walk with the horses. Sometimes walking sticks are handed to travellers climbing without them. Non-Sikh visitors report being invited to sit down for tea and snacks with strangers, made to feel welcome, and told stories about the meaning and history of Hemkunt. Many leave Hemkunt feeling certain that the Sikhs are the friendliest people in India.

Three kilometres above Gobind Ghat, the trail passes Phulna (2,104 m), the winter village of the local people. Bhyundar (2,592 m), their summer village, is passed after five kilometres more. There, the first snow covered peaks come into view. One kilometre above Bhyundar, visitors cross a bridge over the stream and begin the final three kilometre ascent to Gobind Dham. There the path becomes difficult: steep and rocky. Many visitors report being warned before coming that as soon as they cross the bridge they should rest and prepare themselves mentally for the climb. Accordingly, the tea shops clustered just after the bridge do very good business.

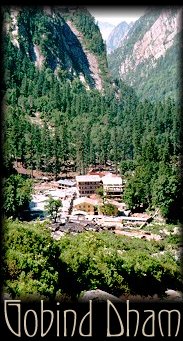

Milestones written in Hindi are installed alongside the path, marking off the twelve kilometres from Gobind Ghat to Ghangaria (3,049 m), known to Sikhs as Gobind Dham. Most visitors take between four and seven hours to complete the trek. The path climbs through dense forests and across an open meadow before the corrugated steel roofs of the village come into view.

Overnight camping is not permitted in the Valley of Flowers National Park, nor are there facilities for pilgrims to stay at Hemkunt Sahib. Therefore, travellers rest for the night in Gobind Dham, the 'abode of Gobind', before beginning their final ascent. The small village is a seasonal business district; there are no homes in Gobind Dham, only lodges and shops. When the Hemkunt Sahib gurdwara opens on or around June first, Gobind Dham opens for business. After the closing ceremonies are performed during the first week of October, Gobind Dham, too, closes for the season.

Only five years ago, the only buildings in Gobind Dham were the government Tourist and Forest

Rest Houses, the Sikh gurdwara, and two or three small shops and restaurants. But as the

number of visitors has multiplied (from 6,050 in 1980 to 189,340 in 1990 according to

gurdwarastatistics), the locals have taken advantage of the growth of the pilgrimage by putting

up numerous new structures. The gurdwara complex, too, continues to expand. There are

now many permanent buildings, and just as many temporary

shelters set up on the periphery of the village by porters and ghora

wallahs. In 1996 there were almost forty restaurants and tea

shops, twenty hotels, and forty-five shops in Gobind Dham. As

they were always opening and closing it was difficult to make an

accurate count. The variety of goods available is surprising,

considering that all supplies must be brought up by mule or

porter.

many permanent buildings, and just as many temporary

shelters set up on the periphery of the village by porters and ghora

wallahs. In 1996 there were almost forty restaurants and tea

shops, twenty hotels, and forty-five shops in Gobind Dham. As

they were always opening and closing it was difficult to make an

accurate count. The variety of goods available is surprising,

considering that all supplies must be brought up by mule or

porter.

The accommodation in Gobind Dham is very basic. In the gurdwara, guests sleep on the cement floors of large, crowded halls or in smaller rooms. In a pinch, the gurdwara can sleep several thousand. Each person is allotted five woolen blankets if there are enough to go around. In June, when Indian students have school holidays and when the weather is clear, the rush to Hemkunt is so great that the gurdwara in Gobind Dham becomes full and staff members shut its gates. The remaining pilgrims are accommodated in shops or on the porches of the hotels and restaurants. On one June day during the 1996 season, more than 10,000 people passed through Gobind Dham, having come to Gobind Ghat in 165 large buses and trucks, as well as more cars and vans and jeeps than I could count.

On an average day, around 1,000 people arrive in Gobind Dham. Many, particularly those from the Indian cities and from abroad, stay in hotels. The hotels have beds and supply heavy cotton quilts, necessary in the minds of most visitors to ward of the unaccustomed chill and dampness of the Himalayan air. With the exception of the dormitories and tents at the government rest houses, most rooms have bathrooms attached. There are no showers. Taps have stream water piped to them and hot water can be purchased in buckets. The price of any one hotel room varies from fifty rupees to 700 rupees depending on the rush. Since the village is only occupied during the summer months, all buildings are unheated. Intermittent electricity is supplied by a turbine which, when the ice and snow have melted by mid- or late-June, is turned by the stream which cascades down from Hemkunt.

Even if they do not stay in the gurdwara, opting instead for relatively more comfortable hotel rooms, many Sikh visitors eat in the langar (free community kitchen) within the gurdwaracompound. Rice, flour, and lentils used to prepare the langar, along with cash to purchase other supplies, are donated by pilgrims. As is common at gurdwaras everywhere, Sikh visitors to Gobind Dham, those who still have enough energy after the journey, take some time to do sea. Usually, that community service takes the form of serving food or cleaning utensils in the langar.

Sikh pilgrims often begin their ascent to Hemkunt before sunrise. At three in the morning, the sleeping halls in the gurdwara suddenly fill with chatter. People move about folding blankets, tying turbans, and dressing children. Some gather for group prayers before they set out; others cluster in the courtyard holding steaming glasses filled with sweet, milky tea. The narrow street outside the gurdwara compound becomes crowded with porters and mules jostling for the business of the visitors who push past them. As they set out from the village, loud cries are raised by groups of Sikhs. One person shouts out "Bole so nihal ...", to which any Sikh within hearing distance replies, with equal force, "Sat Sri Akal!" Non-Sikh visitors often asked me what all the shouting was about. The phrase, which is called a jaikara, or 'victory slogan', means "Anyone who speaks will be happy . . . Timeless God is Truth!"

By 6:30 the street of Gobind Dham becomes quiet again. The only people who remain in the village are the temple staff, the proprietors of the businesses, government workers, and a few visitors who later depart for the Valley of Flowers. Until more visitors begin to arrive from Gobind Ghat in the early afternoon, those left in the village do what is known in local parlance as 'time-pass': they drink tea, gossip, play cards, or snooze.

From the base of the path, those who look up the mountainside can see the saffron-coloured nishan sahib (flag) against the blue of the sky. It stands at the top of the ridge high above, and indicates the location of Gurdwara Sri Hemkunt Sahib. The sight of the flag encourages pilgrims to continue toiling upward; at all times they know how far it is to their destination. The climb to Hemkunt is steep--up all the way. The path has no flat or downhill sections. It zigzags through a forest and then through the high altitude meadows above the tree line. The trail has been cut into the slope, and for most of its length the surface is stone. Even so, during the heavy rains that fall in July and August, it becomes muddy and treacherous. Turning to look out across the valley below, visitors can see snow-covered peaks rising in the distance. More often than not, however, these peaks are obscured by fog and cloud. The rain is unceasing at the height of the monsoon season, and the ascent is wet, slippery, and cold. Tea shops cling to the hillside. At every switchback, people can be seen resting, sitting on rocks or beneath the shelters provided by the shops. Others trudge past them, taking anywhere from two to six hours to cover the six kilometre distance to the holy lake.

As they walk, many Sikhs recite God's name. The chant of "Satnam Waheguru" sets the rhythm for their footsteps. Some jathas travel in procession behind a portable nishan sahib (flag) on a pole topped by a khanda (double-edged sword). Behind it, group members walk carrying drums and cymbals and singing devotional hymns. Even solitary climbers can sometimes be heard singing kirtan, though it is normally sung by groups. Typically, one member sings a line from a song or a shabad (verse from scripture) and the other members repeat it in chorus. A commonly heard shabad, "Charan chalo marag Gobind" means "Walk ye, O my feet, on God's path". Because the appellation used for God in this verse is Gobind, it seems an appropriate shabad to sing along a footpath leading to a place dedicated to the memory of Guru Gobind Singh. The other songs most commonly sung are in praise and remembrance of this Guru, the tenth and penultimate Guru of the Sikhs.

Other Sikhs read from prayer books as they are carried up in kandi baskets or on the backs of mules. Or they stop to read at rest breaks. Small, worn copies of Bachitra Natak, the composition attributed to Guru Gobind Singh in which his meditation at Hemkunt is described, are passed around. Sometimes groups of pilgrims stop at intervals along the trail to offer prayers. Other pilgrims who pass by join in, reciting the words until they have moved out of hearing range. Some pilgrims walk barefoot out of devotion, but there is no expectation that pilgrims should undergo hardship. In the minds of most Sikhs, spiritual benefit is also not attached to fasting, penance, special pilgrim dress, offerings, or rituals.

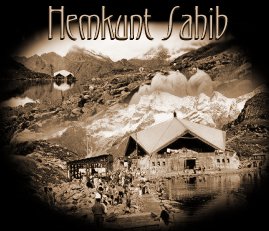

With two kilometres remaining, visitors begin to walk on snow. Many have never seen snow before, so walk slowly and cautiously. A rope has been installed beside the path. People grasp hold of it and jab their walking sticks into the earth. Some scoop up handfuls of the snow and pose for photos. Mules cannot go past the place where the snow begins until enough of it melts to expose the gently sloping switchbacks of the main trail. In June, a slowly moving column of pilgrims and porters can be seen labouring up the almost 1,200 steep stone steps which are an alternate route to the top. Without the sound of the bells around the mules' necks and the whistling, clucking, and shouting of the ghora wallahs, the only sounds that can be heard are the footfalls of the pilgrims, the clatter of walking sticks hitting stones and recitations of "Satnam ... Waheguru". Chants and shouted slogans become more frequent and intense. Those descending jubilantly shout jaikaras which urge on those who are still climbing. Though they become more and more weary toward the end of the climb, the pilgrims feel a tangible excitement with the knowledge that their long sought destination is near. They climb the last few steps, and the saffron flag, the silver roof the gurdwara, and the holy lake itself with its surrounding peaks come into view.

Their sacred journey complete, the pilgrims at last have the cherished darshan (sight) of the sacred place. Many collapse at the top of the stairs and give thanks. Some are overcome with altitude sickness, but most, before the chill of the air at an altitude of 4,329 metres becomes too much, bathe in the water of the lake. Many gurdwaras, especially historical gurdwaras in Punjab, the Sikh homeland, have a sarovar (pond) for bathing in. It is customary for Sikhs to have ishnan (a holy bath) in these sacred waters. Likewise in the natural sarovar at Hemkunt.

The lake, fed by springs and waterfalls, is cold. Until mid June, all but a narrow margin of water along the shore is covered by ice. The men bathe outside after removing their clothes beneath a shelter. For women there is a separate enclosure inside the gurdwara itself: a bath fed by water which flows from Hemkunt and then cascades down the slope toward Gobind Dham. Most enter the frigid water slowly, utter a prayer, then take a series of brisk dips before scampering back to shore. Some pause for a moment to have photos taken to preserve the event. Local youths are on hand to photograph, for a fee, those without cameras.

For most Sikhs, the water of the lake is holy water. It is referred to as amrit (nectar) or jal (holy water). Shops along the route sell plastic bottles which visitors fill when they reach Hemkunt. Once the water is collected, the bottles are sometimes placed inside the gurdwara, just beside the platform on which the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book, rests. Later, after the congregational Ardas has been said, people retrieve their bottles to take home with them. The water is then administered to family and friends in times of sickness.

People like to take some token of the journey home with them to remember it by. That token may be a souvenir purchased from one of the shops. Or it may be a sropa (length of cloth) or parshad (consecrated food) presented by one of the granthis, or perhaps wildflowers collected from the meadows surrounding the lake. These things become treasured reminders of the journey. Sometimes they are given to friends and relations so that those who could not make the journey can feel a spiritual connection with the sacred place, symbolized by the material object.

Other objects are left as donations to the gurdwara. Pilgrims offer blankets, ornaments, food, money, and prayers. Some of these are given in turn to other pilgrims. Donations of ghee(clarified butter), for example, are used to make karah parshad (a sanctified sweet) which is distributed to all. Rumalas (decorated cloths) are sometimes given out as sropas or they, along with wrappings for the nishan sahib flagpole, are given to other gurdwaras. Receipts for donations of 101 rupees or more can be taken down to Gurdwara Gobind Ghat and presented in exchange for orange sropas and dry parshad. These items are given to the absent friends and family members on whose behalf the donations were made. The sropas are often used as turbans on future journeys to sacred places, their saffron colour symbolic of sacrifice.

On a clear day, pilgrims look up and try to count the seven flags atop the seven

peaks which surround Hemkunt. They tell stories about the flags, speculating

about how they came to be there, and how the saffron coloured wrappings on

the flagpoles are changed. They tell other stories as well, about the large

yellow-green blossoms of the Brahma Kamal ('God lotus') flowers which

bloom on the slopes around the lake, about feeling a sense of the Guru's

presence, and about the sacred qualities of the landscape itself. Some Sikhs pay

a visit to the Hindu temple, feeling that God is present everywhere and in

everything, no less in a mandir than in a gurdwara.

On a clear day, pilgrims look up and try to count the seven flags atop the seven

peaks which surround Hemkunt. They tell stories about the flags, speculating

about how they came to be there, and how the saffron coloured wrappings on

the flagpoles are changed. They tell other stories as well, about the large

yellow-green blossoms of the Brahma Kamal ('God lotus') flowers which

bloom on the slopes around the lake, about feeling a sense of the Guru's

presence, and about the sacred qualities of the landscape itself. Some Sikhs pay

a visit to the Hindu temple, feeling that God is present everywhere and in

everything, no less in a mandir than in a gurdwara.

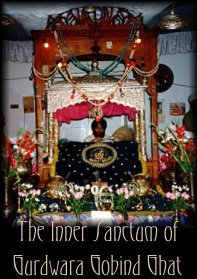

When they enter the gurdwara, visitors have tea, which is poured into stainless steel glasses from great cauldrons simmering over wood fires. Wet, shivering travellers gather around these fires to keep warm. On very cold, foggy days, additional fires are built using wood brought in by mules. When they have had their fill of tea and warmth, visitors remove their shoes, cover their heads, and climb the cement steps to the inner sanctum of the gurdwara. In bare feet they pad across soft carpets and approach the holy book enshrined under a decorated brass canopy.

They press their palms together in prayer, then reach forward, place a donation in cash or in kind before the Guru Granth Sahib, and bow, touching their foreheads to the ground in a demonstration of supplication and respect. They rise, place their hands together once more, and make the parikarma (circumambulation) of the platform on which the sacred scriptures rest. If they have brought offerings of rumalas, silk flowers, brass ornaments, blankets, ghee, or parshad, they present them to the granthi in attendance. Then they sit, wrapped in shawls and blankets, to meditate, pray, read or recite from scripture, or join in the singing of devotional hymns. Some weep from the fatigue of their exertions, or out of joy at finally reaching, by Guru's grace, the place they had long hoped to go.

Two congregational services are held daily at Gurdwara Sri Hemkunt Sahib, the first at ten o'clock and the second at one o'clock. Both centre around the Ardas (the Sikh standard prayer) and the reading of the daily hukamnama (the verse at the top of the left hand page of the Guru Granth Sahib when the book is opened at random; understood to be the command of the Guru for the day). Often, visitors who can sing kirtan seat themselves behind tabla (drums), harmonium (organs), and microphones to sing before the assembled crowd. Their music and voices are broadcast outside of the gurdwara over loudspeakers, and echo across the surface of the water and off of the surrounding rock walls. Before the group prayer, set shabads are sung by the whole of the congregation. Then the granthi takes the microphone, welcomes the congregation to Hemkunt Sahib, and explains the significance of their darshan and ishnan. He relates the story of Hemkunt as it was told in Guru Gobind Singh's autobiography. He then sings, accompanied by all, another shabad as he unfurls donated rumalas over the Guru Granth Sahib, then he moves to stand before it to begin the Ardas.

When it is said at Hemkunt Sahib, the standard Ardas is embellished with references to darshanof the sacred place and ishnan in the holy lake. Special emphasis is also given to Guru Gobind Singh. As in every gurdwara, special prayers are read aloud for individuals and families who have requested them. Most of these prayers are made for the blessing of a son, for a good marriage partner, or for healing. The service concludes as the granthi seats himself again behind the book of scriptures and reads the hukamnama. At the close of every service, volunteers pass out karah parshad, a consecrated sweet made of equal parts of wheat flour, sugar, and ghee, to all members of the congregation. When the auditorium has cleared, several others volunteer to sweep the carpets and fold blankets and rumalas.

Visitors to Hemkunt begin their descent early. The climate at Hemkunt is severe, and facilities are limited, so no one is permitted to stay overnight at the gurdwara aside from the granthis and sevadars (workers who stay throughout the season). By three or four o'clock, only a few visitors remain at the lake. By five they have all started down. Most will reach Gobind Dham before the sun sets. A few, placing unaccustomed feet carefully among the stones on the path, complete their slow downward journey under starlight.