Sikh arts are increasingly in demand by collectors as interest and awareness of this tradition in south Asian culture grows. Based in the Punjab, which encompasses the north-western region of the south Asian sub-continent, the Sikhs are primarily a religious community, now numbering about 24 million world-wide. The essential tenets of Sikhism, the faith that unites them, are set out in the writings of Guru Nanak (1469-1529), the first Guru of the Sikhs, and those of his spiritual successors. He proclaimed that there is one eternal, omnipresent and indefinable God, who is the abstract principle of truth. His followers or disciples, called sisyas or Sikhs, could reach him under the guidance of a Guru. The Guru is the perfect representative of God, through whom the light of God shines. He is not God, but is divine, because God has placed his own spirit into him. The intermediary between God and the Creation, the Guru is the religious teacher of men and the spiritual guide of human consciousness. He shines divine light on the darkness of ignorance.

Guru Nanak defined the ideal person as gurmukh, or one orientated towards the Guru and who practised the threefold discipline of nam-dan-ishnan, meaning the meditation on God’s Name. The three aspects of this are Nam Simran, the relation with God; dan, or alms-giving, the relation with the society; and ishnan, or pure living, the relation with the self that provides a balanced approach for the development of the individual and of society. Guru Nanak stated that in leading the true spiritual life, one should live on what one has earned through hard work and one should share with others the fruit of one’s exertion. Therefore, other ethical virtues, such as service (seva); self- respect (pati); truthful living (sach achar); and humility and sweetness of tongue (haq halal), are all highly valued within the Sikh tradition.

Under the 10th and last Guru, Gobind Singh (1675-1708), the Sikhs were transformed into a potentially self-sufficient military force with a political identity. This was realised within a century of the Guru’s death, under the dynamic leader Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), or the ‘Lion of the Punjab’, the first Sikh Maharaja of the Punjab, who ruled from 1801 to 1839. He conquered, unified and brought peace to the whole of the Punjab and established his court at Lahore. Under his rule the cultural life of the region flourished.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s court was one of the most magnificent in India. When he entertained foreign visitors, scarlet pavilions were set up on gold and silver poles near the river. They were lined with luxurious shawls from Kashmir and their floors were covered in fine carpets. The splendour surrounding the Maharaja of the Punjab is evident in the accounts of travellers and British officials, for whom this was a sight of the utmost exoticism. Sir John Login, guardian of the Maharaja Duleep Singh, wrote to his wife:

“I should say, that for camp-equipage, old Runjeet’s camp was the very finest and most sumptuous amongst all the Princes of India. Now when you are told the tents for him are lined, some with rich Cashmere shawls, some with satin and velvet, embroidered with gold, semianas, carpets, purdahs and floor cloths to match, and that the tent-poles are encased in gold and silver…you may fancy that we shall look rather smart!”

At the centre of all this magnificence was Ranjit Singh, who was small and chose to remain unadorned and plainly dressed. Although his face was disfigured by the childhood smallpox that had left him blind in one eye, he had remarkable energy and personality.

A visitor to the Lahore durbar of 1837, Henry Fane, gave a typical description of Ranjit Singh:

“His dress was almost always the same (green cashmere) and, with the exception of the rows of great pearls before mentioned and on state occasions the Koh-I-Nur, his great diamond, he seldom wore jewels.”

The above image†is a miniature from an album of historical notices by Colonel James Skinner (1778-1841) that includes 37 portraits of princely families in the Sikh and Rajput territories. The portrait of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, rendered with fine, detailed brushwork, depicts him on a throne placed on a carpet viewed in perspective. His blind right eye is discernible. Portraiture is a favourite theme in Sikh painting. The tradition begins with the idealised portraits of the 10 Gurus of Sikhism and illustrations of the Janam Sakhis, the traditional account of the life and travels of the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak. Depictions of the Gurus appear in the Pahari painting tradition, a style of Indian miniature painting developed between the 17th and 19th centuries in sub-Himalayan areas of India. They include the popular image of Guru Gobind Singh as a plumed royal figure on horseback under the umbrella of state, with a hawk on his hand. The painters working for the Sikhs then moved to more topical themes, including the Sikh campaigns against the rulers of the Punjab hill states. Paintings depict them riding as governors through the states or engaged in court ceremonial, from Maharaja Ranjit Singh receiving British delegations to Sikh Khalsa’s durbar of 1838-39.†

The daily needs of the Sikh court in Lahore were supplied by the treasury, the tokshana, in which valuable goods were kept. These included presents received from foreign dignitaries and cash receipts. Figure 2 (below) is a lavishly decorated pair of steel arm defences produced in Lahore in the 19th century, covered with gold and lined with embroidered velvet. These objects illustrate the refinement of the decorative arts and arms and armour of the Sikh courts.

†

Figure 2 Pair of steel arm defences produced in Lahore in the 19th century.

Medals and coins, symbols of wealth and power, were important to Sikh rulers, including Maharaja Ranjit Singh, as tangible, visual indicators legitimising their authority. One such example is a portrait medal produced by the Lahore mint depicting a 12-pointed sunburst star with a portrait of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the centre. It is inscribed on the reverse in Persian, ‘Maharaja Ranjit Singh bahadur Wali-I-Punjab’ – ‘The Victorious Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Punjab.’ This medal was part of an order, ‘The Star of the Prosperity of the Punjab’ or Kaukab-i-iqbal-i-Punjab, created by Ranjit Singh on 8 March 1837 to commemorate the marriage of his grandson Nau Nihal Singh.

A range of craftsmen was attached to the tokshana to produce jewellery for use at court, luxury goods and items for presentation (khil’at). One of the most spectacular artefacts to have survived from the tokshana is the Golden Throne (Fig. 3), the second most famous object connected with Maharaja Ranjit Singh.†

†

Figure 3 The Golden Throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The first was his renowned diamond, the Koh-i Nur, now part of the British Crown Jewels. It was originally set in a gold armlet enamelled in green, white and red (Fig. 4). Ranjit Singh created an atmosphere of religious tolerance within his court. Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs were all appointed to high office and artists and craftsmen worked for patrons regardless of their religious differences. The Golden Throne was made by a Muslim goldsmith, Hafiz Muhammad Multani. It is of historical significance as one of the few royal thrones from the Indian subcontinent to have survived intact. Octagonal in form, its design is based on courtly furniture of the Mughals. Its wood and resin core is covered with sheets of repoussť, chased and engraved gold – unlike European royal furniture, which is usually simply gilded, creating the effect of gold without incurring the cost.†

†

Figure 4 The Koh-I Nur, now part of the British Crown Jewels.The throne’s waisted shape and distinctive cusped base composed of two tiers of lotus petals suggest the lotus seats of Hindu and Buddhist iconography, the lotus being a symbol of purity and creation. It also has eight feet and handles at the narrowest part. The throne has a raised, solid back, with supports on the left and right side, from which tassles hung, and its seat is covered with gold and red cushions.

The Golden Throne was probably made in 1820-30, as recorded in the inventory of the Lahore crown property prepared by John Login immediately after the British annexation of the Punjab in 1849. In 1853 the throne was shipped to London for the East India Company’s museum. It was later transferred to the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert Museum. In the 1850s, the Governor-General, Lord Dalhousie, had the throne copied in mahogany by a Calcutta firm for 678 rupees and 5 annas (then around £67).

By the time Ranjit Singh died in 1839 (Fig. 5), the Sikh kingdom covered the Punjab Hills and Kashmir as well as the Himalayas as far north as Ladakh.†

†

Figure 5 Ranjit Singh’s funeral.

Following his death, there was a struggle for control over the Sikh kingdoms between the Sikh aristocracy and the Hindu rajas of Jammu, the Dogra brothers. The first successor to the Lion of the Punjab was Kharak Singh (Fig. 6), who was followed by his son Nau Nihal Singh and then by his brothers Sher Singh and Duleep Sigh, the last surviving son of Ranjit Singh. Aged only seven, Duleep Singh was the last Maharaja of the Punjab, although actual power lay with the Dogra brothers, most importantly Hira and Gulab Singh.

† †

Figure 6 Maharaja Kharak Singh.

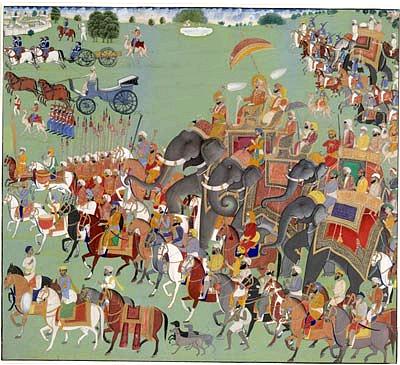

Maharaja Sher Singh, who reigned from 1841 to 1843, is shown together with his son Partap Singh in a large and glorious painting of a royal procession (Fig. 7), riding on sumptuous thrones on top of elephants with royal umbrellas. In the background of the watercolour, painted by a Punjab artist in Lahore around 1850, is the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, in a howdah on an elephant with an attendant waving a flywhisk. The Maharaja’s English carriage and a cannon are also visible.†

†

Figure 7 Maharaja Sher Singh together with his son Partap Singh in a large royal procession.

Sher Singh was an aesthete and anglophile. His active interest in western art affected the tradition of Sikh painting, as he sponsored western artists, such as Herr Schofft; Emily Eden, sister of the Governor-General, Lord Auckland; and Prince Soltykoff. However, before the mid-19th century, he employed Guler and Kangra artists from the Punjab plains.

A Punjab artist painted this procession. Although painting in Punjab is usually thought of essentially as a 19th-century tradition, B.N. Goswamy put forward the suggestion that it went back as far as the 16th century, when the province of Lahore flourished under the Mughals. Paintings in the style associated with the Mughal court were produced in the Punjab through the 17th and 18th centuries. Goswamy has pointed to work done in the 18th century in the late Mughal style in the Punjab plains that depicts characteristic Punjabi themes, such as portraits of the Sikh Gurus rendered in a dry, late-Mughal style, and personages from the classics of Punjabi literature and legends.

At the same time, close to the plains of the Punjab, the great Pahari styles of painting were flourishing in the belt of hill states from Jammu in the west to Sirmur in the east. Here, painters active at the centres of Kangra and Guler, under the patronage of Rajput chiefs, which dominated Pahari painting in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, exerted a powerful stylistic influence on painting in the Punjab plains in terms of mood, line and colouring. According to W.G. Archer, it was in the early 19th century that hill artists began to approach Sikh patrons, at the time that the Sikhs first began to express an interest in paintings.

Sikh portraiture of the 19th century is similar in style and mood to that of the late Guler-Kangra traditions of the Pahari Hill States, notably in such features of Figure 7 as the tonality of cool green and the general palette of the painting, the flattened background with a slight horizon with globular clouds and the use of profile in rendering the figures, who are depicted with elongated eyes. These all derive from the style of the Guler artists brought from the Hill states of Punjab to their new Sikh patrons in the two main centres for Sikh painting, Amritsar and Lahore.

The main figures in this painting as well as the elephants, their trappings and the horsemen are all sensitively rendered in a late-Mughal style filtered through Pahari influence, with attention focused on the modelling of individual features. This very observant approach to painting figures, with an emphasis on the personality of the individual, as opposed to generic paintings of rulers, was introduced to Sikh art from the Guler tradition by the Guler artist Nainsukh and his workshop, which included his son Nikka and Nikka’s three sons, Gokal, Harkhu and Chhajju.

There is documentary evidence that Gokal worked for Maharaja Sher Singh. Fine, detailed brushwork is characteristic of this style of painting, noticeably in the treatment of beards, which are rendered with delicate strokes, and costumes and textiles, including those that drape the elephants, and turbans and other headgear. The execution, while delicate and sensitive, has a tendency towards simplification, especially in the treatment of the landscape settings.

Sher Singh is depicted with a halo, a motif derived from the depiction of Mughal emperors in Mughal paintings. It first appears in Sikh portraiture in depictions of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The umbrellas above the Maharaja and his son are also symbols of sovereignty. They are large compared to the depiction of royal umbrellas in the Pahari tradition, to convey an additional sense of grandeur.

Other identifiable figures in the painting include, in the howdah of the third elephant, the prominent Sikh generals Sham Singh Atariwala and Tej Singh Bahadur. In the fourth howdah is Raja Dhian Singh, a supporter of Sher Singh and Wazir. Partap Singh, shown in the howdah of the second elephant, was a remarkable boy who was murdered at the age of 12 with his father and brother Dhian Singh by the Sindhanwalia faction in the garden of Sardar Jawala Singh Padhani in 1843.

Processional scenes depicted in 19th-century Indian paintings include conveyances used by or given to the ruler. The carriage here is perhaps that presented with four mares by the British Government to Ranjit Singh by Captain Alexander Burnes in Lahore on 18 July 1831, together with a letter from King William IV. The cannon is possibly one of the two presented to Ranjit Singh by Lord William Cavendish Bentinck at their meeting in Rupar on 31 October 1831, each drawn by six horses, although there is no mention of cannon in the official list of gifts submitted to London, which mentions only guns and pistols and pieces of cloth.8 Similarly, Lord Auckland presented two howitzers on 30 November 1838. The painting shows a type of cannon, copied from a British model, which inflicted heavy losses on British troops during the Anglo-Sikh wars.

The different sections in the Sikh armed forces that are depicted can be distinguished by their head- gear, uniforms, weapons and horses – the artillerymen servicing the cannon at the top left corner all wear blue uniforms. Other troops wear the red jackets with blue trousers and turbans of the Sikh infantry. The horsemen protecting the Guru Granth Sahib at the top right corner wear blue jackets and turbans and white trousers with a yellow scarf round their waists and Sher Singh’s personal guard in the main body of the painting wears crimson.

Preoccupation with portraiture carried on well into the interregnum that preceded the final annexation of the Punjab in 1849 by the British. Painters were officially employed at the Sikh durbar at Lahore in 1838-39 to depict the rulers of the Punjab Hill States, and portraits of Indians were also commissioned by Europeans living in the Punjab. On 26 December 1846, Britain and and the Sikh rulers of the Punjab signed the Treaty of Lahore, bringing to an end the first Anglo-Sikh war (1845-46). The scene was recorded by a Punjabi artist (Fig. 8).

† †

Figure 8 Signing of the Treaty of Lahore.

The cultural history of the Sikhs encompasses a variety of artistic media, including paintings of the Maharajas and their families, provincial paintings produced throughout the Punjab and manuscript miniature painting. Arms and armour, jewellery, coins and medals, decorative and ethnographic arts, notably textiles, round out a rich cultural legacy that is still being developed by contemporary Sikh artists.

| Written by Jasleen Kandhari, Apollo Magazine †† |

| Monday, 17 March 2008

(First published Apollo Magazine, Friday, 2nd November 2007) |

About the author: Jasleen Kandhari is the Curator of Asia at the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

† |

![]()